Lisa Matthews, Coordinator at Right to Remain, reflects on the legacy of the slave trade in Liverpool and inspiring anti-racist campaigners today.

I was in Liverpool yesterday to celebrate the good news that a friend has won her long battle for justice, for her right to remain in the UK. It’s so important to cherish these moments of joy, even though they are tempered by anger at the years she has lost and the abuse she has suffered, and the sadness that those who were celebrating with us are still waiting, still fighting.

It was with these thoughts in my head that I revisited the International Slavery Museum.

It’s been some years since I last visited, and I was struck by how the museum still seems to have to vie for attention in the Albert Dock. I had actually forgotten that the museum isn’t a stand alone institution but housed by the Maritime Museum (and therefore is left off signposts in the city, at least the ones I passed). Perhaps this hosting means the museum reaches new audiences, people who might not necessarily seek out a museum that examines Liverpool’s role in the transatlantic slave trade. But I did wonder how many non-determined visitors would make it up to the third floor of the museum, with exhibitions on the sinking of the Lusitania and the Titanic seemingly receiving far more prominence.

These concerns notwithstanding, the museum is very impressive. It does not flinch from Liverpool’s role in the horrors of the slave trade (Liverpool ships were responsible for 10% of all enslaved Africans). It encourages you to look out at the docks where the slave ships loaded up before heading to Africa. It highlights places in the city built with the riches of slavers. And it’s timeline gives prominence to the slave revolts that were so crucial to ending the barbaric trade, rather than obsessing about white abolitionism which some other heritage sites are guilty of.

Past and present are constantly connected, and there is a broad appraisal of the legacy of the slave trade in the form of white supremacism, structural and societal racism and socio-economic inequalities.

The museum does great work linking up these histories to slavery, persecution and injustice today. They have worked closely with the brilliant group Mama, a support and solidarity group in the city made up of mostly asylum-seeking women, with whom we have shared struggles and successes over many years now.

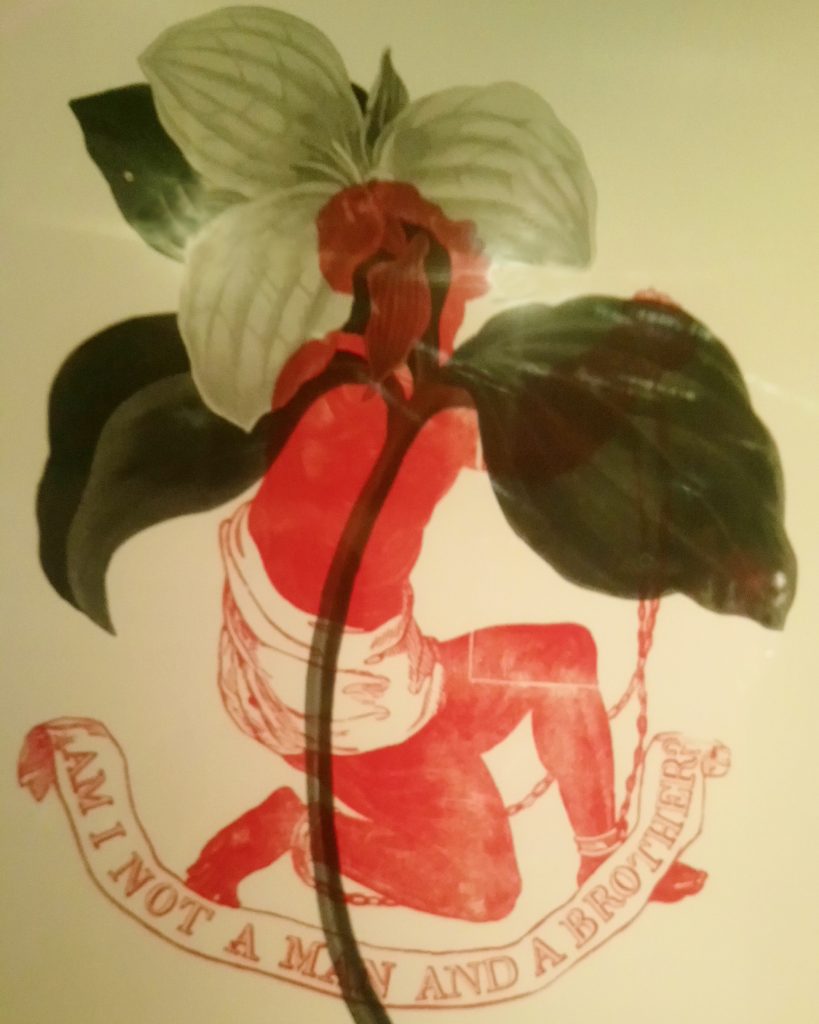

I was really struck by a small poster exhibition by Calum Jones which evoked the sites of entanglement between Liverpool and the slave trade. One poster combined the famous Josiah Wedgwood image used as a symbol of the abolition movement with an okra flower. Okra was one of the few plants indigenous to Africa that was brought by enslaved Africans and grown in the Americans and the Caribbean. The poster notes explain that because the plant subsidised the meagre diet given to enslaved Africans, it can be viewed as “a symbol of both cultural resistance and survival”.

These themes of resistance and survival are at the heart of the work done by Mama (and are beautifully expressed in their fundraising book, “Strategies for Survival, Recipes for Resistance”) and the other asylum and migrant solidarity groups across the UK.

For me, the slavery museum will always have another special connection too. On the day of a refugee rights demo led by Eritreans in the UK back in 2015, hundreds of people assembled at the docks in Liverpool to march to the Home Office to protest at their treatment of asylum claims. Security guards tried to tell protesters to keep away from the grounds of the Slavery Museum, only to be challenged by one of the protest organisers, a black Scouse woman, who said “How dare you! This belongs to us – our ancestors died so that these stones could be laid”.

Discussion: