By Lisa Matthews, Coordinator at Right to Remain

Last week, a charter flight deported thirteen people to Jamaica. Because of emergency legal interventions, this is many less than the Home Office had intended, but is still thirteen lives torn apart.

Deportations to Jamaica are nothing new, but the level of opposition to them have been growing. In the wake of the Windrush scandal, the then Home Secretary Sajid Javid announced that charter flight deportations to Jamaica would be paused. Then they were quietly restarted.

It is has been heartening to see increased campaigning against the deportations – mobilising against these flights in the past rarely extended beyond a small but committed number of activists. The actions of the Stansted 15 and the shockwaves of the Windrush scandal have raised awareness of these deportations and this can only be something to celebrate. That’s not to say that opposition is widespread, however. The deportation of “foreign criminals” remains a broadly popular measure, and the right-wing press coverage of the deportation flights consistently emphasise the view that the people being deported have committed “serious” and “violent” crimes.

A last minute concession to the campaigning did seem to have been achieved on the latest deportation flight. The Guardian reported that the Jamaican government were unwilling to receive people who had arrived in the UK before the age of 12.

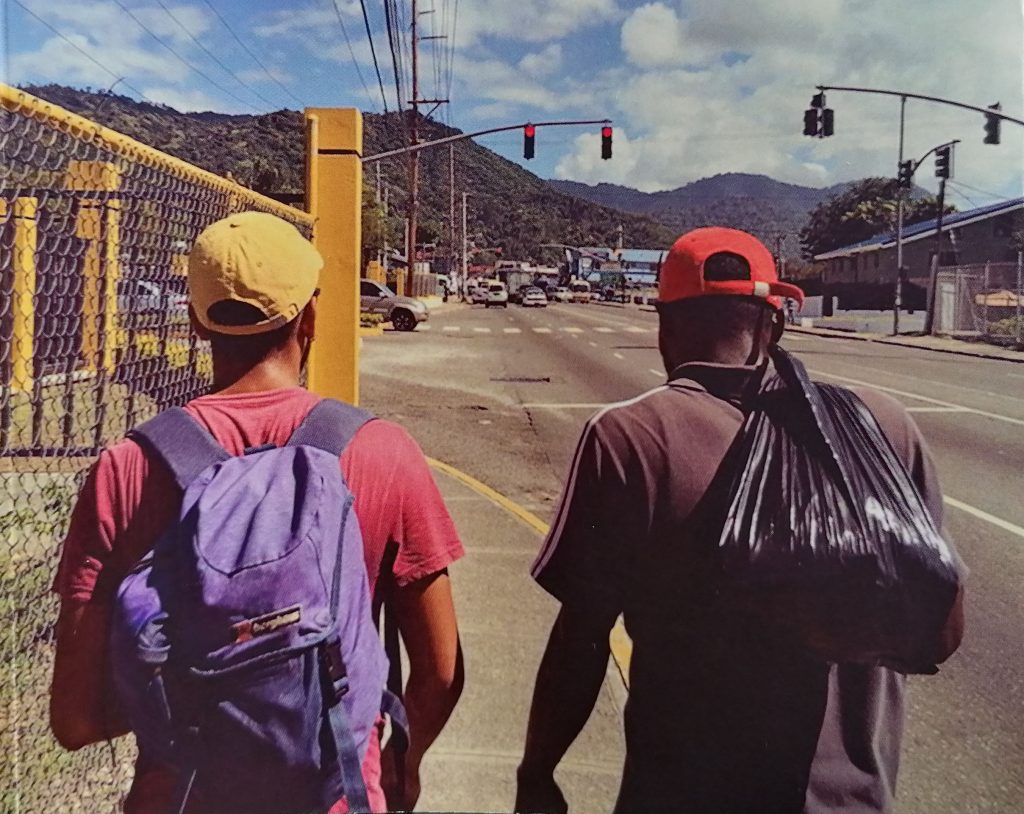

Ricardo would have benefited from this concession, but Jason, Chris and Denico would have been excluded. These four men are the protagonists of Luke de Noronha’s book, Deporting Black Britons. Portraits of deportation to Jamaica (Manchester University Press).

Through the stories and lives of these four men, de Noronha explores the human impact of the UK’s deportation policy (and Jamaica’s compliance with it) and thematic aspects of state racism.

Jason, Ricardo, Chris and Denico

In the chapter on Jason, we hear about his experiences of racism in the UK, and de Noronha draws together the interactions between Jason’s racialisation and his poverty. Jason was hypervisible because he was street homeless – and he was street homeless because of restrictive immigration policies. Jason’s narrative demonstrate that “immigration and citizenship status often determine how racism get’s into people’s lives”.

Ricardo’s story is one of truly shocking picture of police harassment. Ricardo was “arrested over 100 times and always NFA’d … They used to hassle me differently fam, always arresting me for no reason”. Ricardo’s individual experiences are used to explore the connection between racist policing and immigration control. De Noronha complicates this picture through highlighting Ricardo’s non-straightforward understanding of policing and racism – he points out that Ricardo (and Jason) lived race through class, age, gender and place and “as such, racism was both unremarkable (i.e. just part of life) and hard to isolate and name”. Through an interview with one of Ricardo’s friends in the UK – Melissa – the author further analyses the interplay between race and immigration control and concludes:

“immigration controls do not simply exclude racially undesirable migrants, they also define the very terms of racial differentiation and exclusion in the first instance”.

Deporting Black Britons reveals the extreme hardship that people deported from the UK to Jamaica experience, but is mindful not to homogenise those experiences. Ricardo’s chapter concludes with the uplifting update that Ricardo is expecting a child with his partner Tinesha – “Ricardo is actually doing well now. His life in Jamaica is full and hopeful and deportation was as much a beginning as an end”.

Chris’ chapter – as well as exploring his personal history – argues that the UK deports people who are too well integrated, as opposed to not integrated enough (as deportation policy professes). De Noronha states that:

“criminalisation and deportation operate to individualise and externalise wider forms of inequality and violence, thereby obscuring broader causes of social harm”. Or, as Chris puts it “England made me a criminal”.

This section of the book has a particularly insightful analysis of integration, and how it “functions primarily as a codeword for racial anxieties and resentments; integration is about ‘what we do with them’. The chapter is also helpfully nuanced, acknowledging Chris’ flaws while situation them in a context of unequal, racist and sexist social settings.

The final individual-centred chapter is about Denico and is a compelling examination of how “family norms are defined and enforced at the border”. It’s worth quoting at length how a snapshot into someone else’s life – Darel – lays bare this phenomenon:

“As in Denico’s case, Darel was not the ‘breadwinner’. He was the primary carer for four of his children, in no small part because his immigration status prevented him from working. The fact that he was deported in spite of this care work demonstrates the invisibility of, and low value accorded to, reproductive labour. Feminists have long made this argument in relation to women’s unpaid labour, and here we see the undervaluing of care work when performed by poor black men. Gendered narratives on men’s patriarchal responsibility to ‘provide’ – and the related assumption that care work performed by men is always secondary to that of the mother – have profound implications in deportation cases”.

The chapter shows how immigration control necessitates a form of performance to try and meet the criteria of immigration policy, following a “heteronormative and nuclear family” script. De Noronha continues to push back against this restrictive framework in his concluding chapter, pointing to the importance of friendship in all of the narratives, and how these friendships were “illegible and irrelevant within immigration law”.

A highly recommended read

Anyone who has followed Luke’s interventions over the years will not be surprised at the quality of writing and scholarship evident in this book. The overwhelming sense of this book is one of humanity – the focus on “portraiture … biography” made the book really come alive for me, and the ethics of direct representation from those featured in the book permeates throughout, including an Afterword by Chris. This book has deepened and refined my knowledge and thinking on a topic that occupies my thoughts a great deal, and for that I am thankful.

I am also grateful for the optimism that is achieved in the final pages (despite an unflinching portrayal of racist and cruel practices in the UK, and often heartbreaking trajectories once some of the characters are deported to Jamaica). De Noronha notes that “amid the damage of racism and nationalism, there are always connections being built, friendships being made and boundaries being crossed.” We must hold on to this. In this current political climate, when winning meaningful policy reform on deportation seems a challenge, we need such mantras of hope to sustain our building towards radical change.

Discussion: