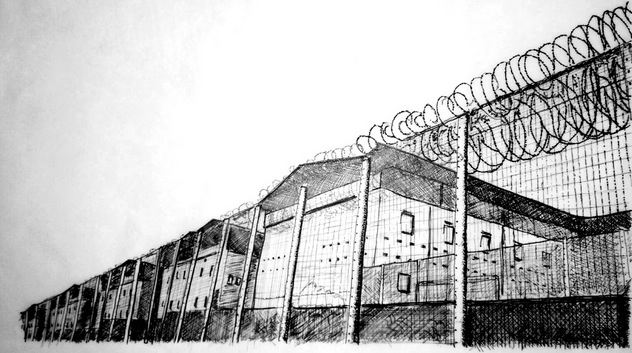

In 2001, Parliament introduced the Detention Centre Rules for the “regulation and management” of immigration detention centres. Rules 34 and 35 introduced mechanisms to try and ensure that people with independent evidence of torture were not detained, except in very exceptional circumstances.

These rules stipulate that within 24 hours of entering a detention centre, the person must have a medical examination and that detention centre doctors must report to the Home Office any concerns that the person has experienced torture.

What is torture?

Until 12 September 2016, the definition of torture used in the context of survivors of torture and immigration detention was:

The use of this definition of torture in the context of Rule 35 was confirmed in the legal case of R (EO) v SSHD [2013] EWHC 1236 (Admin).

The United Nations Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment (UNCAT) specifies that this severe pain or suffering, to be torture, must be “inflicted by or at the instigation of or with the consent or acquiescence of a public official or other person acting in an official capacity”.

The UK Home Office began using the UNCAT definition – the more restrictive one – from 12 September 2016.

There are long-standing issues with inadequate application of Rule 35 in detention, consistently recorded and challenged by the organisation Medical Justice. See, for example, their 2012 report, “The Second Torture”. These issues have included people indicating they have experienced torture, but this not being recorded by detention centre doctors, or recorded poorly. And even when these have been recorded, Home Office caseworkers have ignored or refuted these reports.

Survivors of torture have been routinely detained, despite Home Office policy explicitly stating the opposite should occur.

Medical Justice reported that in late 2015 and during the course of 2016 there were some improvements in the quality of Rule 35 reports and Home Office responses. For the year ending June 2016, 30% of Rule 35 reports led to release from detention, whereas in 2013 and in the first half of 2014, approximately 9% of rule 35 reports led to releases.

The Shaw Review and the Adults at Risk policy

In February 2015, it was announced that the Home Secretary had commissioned a review, led by Stephen Shaw of the welfare in detention of “Vulnerable Persons”.

The report of the Shaw Review was made public in January 2016. The review found, amongst other things, that safeguards for vulnerable people were insufficient to protect them, and called on the Home Office to “immediately consider an alternative to the rule 35 mechanism”.

The then-Immigration Minister James Brokenshire responded by saying that they accept “the broad thrust of [Shaw’s] recommendations and”

“accepts Mr Shaw’s recommendations to adopt a wider wider definition of those at risk will be introduced, including victims of sexual violence, individuals with mental health issues, pregnant women, those with learning difficulties, post-traumatic stress disorder and elderly people, and to recognise the dynamic nature of vulnerabilities. A new “adult at risk” concept will be introduced into decision-making on immigration detention with a clear presumption that people who are at risk should not be detained.”

The government then developed an “Adults at Risk in immigration detention” policy. A draft version of the policy was made public, and then a further draft was laid before Parliament.

As the lawyers Bhatt Murphy make clear in their legal briefing, during the announcement and in drafting the first version of the policy,

At no point did the Home Office mention, still less consult upon, changing the definition of torture to the UNCAT definition…

[The subsequent draft] was laid shortly before the summer recess and the Home Office did not explain that the policy adopted a more restrictive definition of torture than current policy. On the contrary, Ministers repeatedly stated in Parliament that the policy would build on existing policies and provide greater protection to vulnerable individuals.

The adults at risk policy was brought into force on 12 September 2016, and contains the restrictive definition of torture.

Medical Justice argued that “the UNCAT definition of torture is very technical and is likely to be applied by caseworkers and doctors in such a manner as to exclude cases of non-state torture”.

This meant that from 12 September, Rule 35 reports which are intended to prevent people who had experienced torture from being detained, would not succeed if the person could not provide independent evidence of having being tortured by state actors (or with their consent/acquiescence).

Medical Justice also argued that “the policy relies on mechanisms that have been demonstrated by the Shaw review to be ineffective, it limits the definition of torture to acts carried out by state actors and requires victims of torture to present evidence that they are being harmed by detention in addition to proving a history of torture.” Read more here.

Legal challenges

Medical Justice, Duncan Lewis solicitors and Bhatt Murphy solicitors all brought legal challenges to this change.

Who would be affected by the change? One of the examples of the cases linked in the legal challenge was:

an Afghan man in his early 20s who was reportedly kidnapped and tortured by the Taliban because he refused to be groomed into joining them. The Afghan man was beaten with knives, sticks and a gun, and the court heard his injuries are consistent with his account… the Home Office told him his case did not meet the new definition of torture.

The lawyers argued that when doctors were preparing Rule 35 reports using the pre-September definition of torture (the broader definition), the Home Office response was simply that the individuals fell outside of the adults at risk policy because the torture did not meet the UNCAT definition. Doctors were also not even sending Rule 35 reports, because the individual’s account of torture did not in the doctor’s opinion meet the UNCAT definition.

The Home Office argued that if victims of non-state torture found not to meet the UNCAT definition are or are likely to be harmed by detention, other parts of the Adults at Risk policy provides protection.

In the 5 cases brought by Duncan Lewis and the 2 cases represented by Bhatt Murphy, the Home Office conceded that the individual responses to Rule 35 reports had been unlawful on the basis that they had not properly applied the adults at risk guidance.

This raises the age old issue of, even if a Home Office policy on paper provides protection that meets with legal requirements, it is the application (or lack of) those policies that tend to lead to unlawful practice by the Home Office. The more restrictive the definitions and therefore the protections included in these policies, surely the more likely this is to happen.

Medical Justice’s legal challenge – a judicial review of the Adults at Risk policy on the basis that it fundamentally weakens protections for vulnerable victims of torture – was given permission to proceed and a full hearing will take place in March 2017.

“Interim relief” was granted in Duncan Lewis’ application, meaning that the Home Office must for the time being use the pre-September definition of torture (not restricted to torture inflicted by state actors).

An important legal decision will therefore be made in March, which may reinstate vital protection for the survivors of torture. Vulnerable people should never be detained. Join Right to Remain in calling for an end to immigration detention altogether.

Discussion: