In the latest in our series, our management committee member Catherine Hurley talks about her experience with, and resistance to, the UK’s ‘hostile environment’ immigration policies.

(Catherine, middle, at a Right to Remain meeting)

My first brush with the hostile environment was when, as a university administrator, I had to deal with the petty and acutely frustrating recruitment rules for hiring international researchers. This involved complicated instructions about screen shots of ads that I mistakenly assumed could not be serious until we were told in no uncertain terms that we’d have to re-run the recruitment process. My university set up a whole department within Human Resources – the Compliance Dept – to ensure it stayed onside of what was then called the UK Border Agency (UKBA). Immigration compliance rules were strictly enforced. It was uncomfortable and, frankly, shameful to be involved with a system that subjected ordinary people to such indignities.

But the hostile environment was much, much harsher to people coming to the UK without the sponsorship of an employer. Refugees, asylum seekers and other migrants who could not prove to the Home Office’s brutal satisfaction that they should be granted leave to remain could be detained and deported. Or just detained, indefinitely, as it has turned out. While originally set up to be the final stage before deportation, in 2017 55% of people detained were released back into the community, not deported. That’s more than 15,000 people held in detention for no apparent purpose.

“As a relative newcomer, I have learned such a lot from people who have been fighting for migration justice for a decade or more.”

Although scandals such as Windrush bring the shocking details of the hostile environment to public attention – for example, the Home Office requirement that people produce 4 pieces of proof of residence for every year they’ve been in the country – the government continues to defend the so-called deterrent policies in the name of keeping ‘illegal’ migrants out. The UK’s system of immigration detention repeatedly draws criticism from international bodies such as the UNHCR and, only recently, the system of indefinitely detaining asylum seekers who had arrived via another EU country was declared unlawful by the court of appeal. Meanwhile, the Home Office under successive Home Secretaries seems willing only to make superficial changes, like rechristening it a ‘compliant environment’.

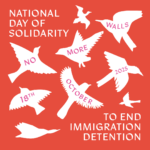

I am thankful that as I learned more about the hostile environment and immigration detention, I also discovered Right to Remain, via an Amnesty organized workshop at which Lisa Matthews gave a session on the realities of immigration detention. Here was a group of people who were not only providing resistance but also invaluable aid to people caught up in this hideous system. I am proud to be a small part of the fight for migration justice by lending a hand on the management board of Right to Remain. Immigration detention and the other manifestations of Theresa May’s hostile environment are what’s turned me, late on, into a protestor, activist and – most unbelievably to me – a social media volunteer for another amazing organization, the Detention Forum.

There are glimmers that the work of organisations such as Right to Remain and many others is beginning to have an impact and we can maybe hope for an end to the hostile environment. As a relative newcomer, I have learned such a lot from people who have been fighting for migration justice for a decade or more. And this is one of the most powerful lessons: In the words of Eiri Ohtani, Director of the Detention Forum: “If you want social justice, you need to master hope: it’s our professional and moral requirement.”

Catherine has worked at the University of Cambridge’s interdisciplinary research centre, CRASSH, for the last 15 years. She has recently become active with organisations concerned with immigration and asylum in a voluntary capacity. She emigrated to Canada from the UK with her family as a baby but has only recently begun to think of herself as an immigrant.

Discussion: