By Lisa Matthews, Coordinator at Right to Remain.

The last few weeks has been a flurry of workshops. Some of these have been on understanding the asylum/immigration process (based on our Toolkit, a unique guide to navigating the legal process and taking action for the right to remain), such as the session last week with Rene Cassin, Glasgow the night before that and the session we’re running in Swansea on Thursday. Others have been focusing on immigration detention – what it is, why it’s bad, and how to get involved in campaigning against it.

As I’ve written previously, we’ve been running a lot of these sessions with potential campaigners – allies to those at risk of detention, but not at risk themselves.

Two of the workshops we’ve run in the last few weeks have been solely with those who have experienced or are at risk of detention – people who do not currently have the right to remain in the UK.

On Sunday, I ran a workshop with members of Akwaaba, a weekly drop-in in London. It was a small workshop, but a really powerful one.

Thank you @Right_to_Remain for an amazing workshop on Sunday. Everybody loved it! See you at #Yarlswood on 3/12! #Detention #ShutItDown

— Akwaaba (@AkwaabaHackney) November 15, 2016

Although the main purpose of the workshop was to talk about detention campaigning and how to get involved, when you’re running a session with people at risk of being detained at any moment, it becomes necessary to address the practical side of things too – when can you be detained, and how can you prepare in case this happens (we have a section in our Toolkit on just this).

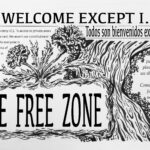

Image: Michael Collins, Right to Remain

What’s become abundantly clear in the workshops we’ve been running, and in the support work with grassroots asylum/migrant groups in general, is just how little is known about immigration detention in the community of ‘those at risk’. For those in the sessions who have experienced detention already, many speak of how the first they knew of it was when they were taken to detention itself. Others in the room speak of how the phrase “immigration detention” terrifies them, but they don’t know what it means and what to do about it. (I asked people to draw what the words “immigration detention” conjure up, and you can see one example of that at the top of the post – which highlights this theme of not knowing). Some phrase it extremely eloquently, such as the person who said about the workshop: “It was like I’ve been blind for years, and now I can see”.

One of the things I asked people to do in the workshop was name the UK’s detention centres (and then place them on a terribly-drawn map of the UK I had made. It was obvious why our artwork is produced by my colleague Michael and not me!).

“Yarl’s Wood” of course, the first to be named. “Colnbrook” said a woman, correctly naming one of the other sites of the detention of women, which not many people know. “The Verne” said one, pointing at the dot off Weymouth, perhaps the most isolated off all the UK’s detention centres. “Are they all in England?!” asked one woman. “Almost” I replied, blu-tacking up the name of Dungavel in Scotland, which the Home Office announced will close by the end of next year, and plans to build a new short-term centre near Glasgow airport have just been stymied by campaigners.

The names of Harmondsworth, Tinsley House, Brook House, Campsfield House, Morton Hall all went unmentioned and did not strike a chord when I listed them. Of course, those who have been detained in these centres know these names. But what is remarkable is how many of these sites of detention remain hidden, unspoken, amongst the people who could be locked-up there, indefinitely, simply for not having the right immigration papers.

The project we co-run, Unlocking Detention, wants to change this. We want these centres known, name-and-shamed. Mapped, visited, lit up, exposed. Helping people who are at risk of detention understand how awful it is, is not a straightforward process. We need to engage people, inform people, without scaring people away or traumatising people even further. But the people who are most affected by this outrage must be informed, must know that all possible practical solidarity actions are being taken to protect them from detention and help them if they are detained, and we all must be emboldened to take this campaign into our streets (the streets that people are disappeared from, taken far away from detention) and get our neighbours, friends, families to stand together to say no to detention. There are many eyes to open.

Right to Remain is co-hosting a public meeting on campaigning against detention in Manchester on 30 November. Follow us on Twitter, like our page on Facebook or sign up for our emails to find out about our workshops and events across the UK.

Discussion: