Last updated: 26 January 2026

Immigration Enforcement (IE) is the part of the Home Office that carries out immigration control. It says its job is to “protect” the public and economy, but in practice this means surveillance, control, and removal through reporting, raids, detention, and deportation that often target people already facing hardship and discrimination.

These teams are part of the UK’s wider Hostile Environment, which pushes border checks into everyday life: into homes, workplaces, hospitals, schools, and banks. It forces landlords, employers, and public services to carry out immigration checks and turns spaces that should offer care and safety into places of control.

This guide focuses on the enforcement carried out directly by the state, especially reporting and immigration raids; two of the most common ways people are controlled and detained. We know from our communities the fear, uncertainty, and disruption these cause, but also the strength and solidarity that we can grow in response.

Within the guide, you’ll find clear, practical information about what these enforcement practices are, who they affect, and how to be prepared – including your rights, risks, and steps you can take to stay safe, supported, and informed.

Who works in Immigration Enforcement?

The Home Office uses several different teams for enforcement. Some plan raids, some carry them out, some run reporting centres, and others make decisions on detention and removal. Understanding who does what helps communities protect themselves.

- Immigration Compliance and Enforcement (ICE) – frontline teams who carry out raids on homes and workplaces, ask questions, check documents, and detain people.

- Reporting and Offender Management (ROM) – the staff who run reporting centres, monitor people on immigration bail, and decide if someone should be detained at reporting.

- Casework Teams – Home Office staff who make decisions on people’s immigration cases, including detention, removal and deportation.

- Criminal and Financial Investigation (CFI) – officers who investigate organised immigration-related crime such as trafficking, smuggling or document fraud.

- Intelligence Units – teams who collect and share information about people, workplaces or networks to plan enforcement operations.

- International Intelligence Network – staff based outside the UK who work with other countries to stop people travelling to the UK.

- Detention and Escort Services (DES) – teams who run immigration detention centres and organise transport for removals, including charter flights.

What is immigration bail?

Being on immigration bail means you are not in detention, but you are still under Home Office control and must follow strict conditions.

Immigration bail is permission to be in the UK under certain conditions while your immigration case is being decided, or after you leave detention. You are still “liable to detention”, which means you could be detained again if the Home Office decides to take further action on your case.

Common bail conditions include:

- living at a specified address

- reporting regularly to the Home Office or police

- restrictions on work, study, or travel

- sometimes wearing an electronic tag (GPS monitor)

You’ll receive these conditions in writing on your Bail 201 form. This is a formal letter from the Home Office that clearly shows your details and bail conditions, includes your Home Office reference number, and is headed “Bail 201”.

You should take your Bail 201 form with you to reporting appointments.The Home Office calls these appointments “reporting events”.

What is reporting?

Reporting is an immigration bail condition. It means keeping in contact with the Home Office while your immigration case is still being decided. Reporting is managed by the Reporting and Offender Management (ROM) teams within Immigration Enforcement (IE).

Many people call reporting “signing” because, for many years, people had to sign their name in a book or on a form each time they reported. Even though many centres now use computers or phone check-ins, the word “signing” is still widely used in communities. In this Key Guide, we will use the term reporting.

You may be asked to report in person, by telephone, or through digital reporting (usually email or via an app). The purpose of reporting is to show that the Home Office can contact you and that you are following your bail conditions.

Full details can be found in the Home Office Policy on Reporting and Offender Management v.8 (October 2025). This guidance explains how staff manage reporting, how they decide reporting conditions, and how they keep in contact with people on immigration bail.

Where do people report?

People required to report in person must attend the nearest Home Office reporting centre or another location specified on their Bail 201 form, or sometimes a police station.

There is no maximum distance set in law, but the Home Office should consider the impact of long travel times (over two hours each way) and take account of people who are young, elderly, vulnerable, or have medical issues.

If travel is difficult, staff can direct someone to report at a closer police station or by phone or digital reporting, though some events (for example, interviews) may still require travel to a main centre.

There are currently 13 dedicated reporting centres across the UK:

- London & South: West London, South London

- North, Midlands & Wales: Liverpool, Manchester, Leeds, Sheffield, Solihull, Loughborough, Cardiff, Swansea, Middlesbrough

- Scotland & Northern Ireland: Glasgow, Belfast

- Reporting also takes place in some police stations, including areas such as Hampshire, Thames Valley, Devon and Cornwall, the South West, and the East of England. A ROM manager may also require someone to report at a police station instead of a Home Office centre. For example, if there has been a problem with aggressive behaviour, a criminal offence, or where the case is being prioritised for removal or enforcement.

These centres are also where you may go for other interviews about your case such as your screening interview in order to claim asylum, your substantive asylum interview, or for documentation or emergency travel document interviews.

You can find updated contact details of all the reporting centres on the UK Government website here.

Different ways to report

In-person reporting

If you have to report in person, you will be told to go to a Home Office reporting centre (or sometimes a police station) at a specific time and date. You will receive the appointment by text, email, or letter. The Home Office calls these appointments “reporting events.”

You should only attend if you have an appointment. When you arrive, you may have to queue at the entrance. You will show your text message and/or Bail 201 form to the security staff at the door. You will then go through security checks, where your bag is put through an X-ray machine and you walk through a metal detector. Inside, staff will check your identity, and you may be asked a few short questions about your current circumstances.

Sometimes reporting is quick. Other times, you may be asked to stay longer for an interview. You may be at risk of detention when you report in some situations.

It is important that you bring your Bail 201 form and the SMS text message or email confirming your appointment each time you go to report. Read more about the challenges you might face with in-person reporting here.

Telephone reporting

Telephone reporting is when the Home Office calls you at a certain date and time. You will have details of when you are expected to receive a telephone call on your Bail 201 form. You will get a text message to remind you of your next reporting time.

You will usually receive a call from this phone number: 0300 1050321. You must answer the phone yourself. No one else is allowed to answer for you – not a friend, family member, legal adviser or solicitor. When you answer the call, the Home Office staff member will ask you some questions to check your identity. The call may also include personal questions, so try to be somewhere private, and somewhere you are able to access any important information or paperwork about your case.

If you do not answer the planned phone calls, and the Home Office cannot reach you after trying again, they will say you have not followed your immigration bail rules. The Home Office will try to contact you (or your legal representative) within 72 hours after the missed call. If you still do not answer after these attempts, the Home Office may take further action. For example, they will tell you to start going to the reporting centre in person.

Immigration Bail Digital reporting (IBDR)

Immigration Bail Digital Reporting (IBDR) is a digital way of checking in with the Home Office while you are on immigration bail. Instead of travelling to a reporting centre, you confirm your compliance by replying to a message sent to your phone or email. This can either replace your usual reporting condition or be added alongside it.

If you are given an IBDR condition, the Home Office will contact you directly by email or text message with instructions. You must reply yourself by following the link or prompt in that message. You should reply to IBDR messages yourself using your own phone or email (unless you’ve been told to report as part of a family group). You can still speak to your lawyer, caseworker or community for advice, but they cannot reply to the Home Office on your behalf for digital reporting. Sometimes the Home Office will ask you to share your location when you report digitally. This just means letting your phone show where you are at that moment so they can confirm you’ve reported.

If you don’t reply to a digital reporting message (and any of their follow-up reminders), the Home Office may count it as a missed check-in (“breaching your bail conditions”) and ask you to start reporting in person again.

When you report online through IBDR, the system uses small files called cookies. These help the Home Office link your digital reporting to your own phone or device and check that the same phone isn’t being used to report for someone else. Simply, it’s a way for the system to confirm who’s reporting and from which device. You don’t need to do anything about it, but it’s important to use your own phone or email for reporting and not share it with anyone else.

If you lose access to your phone or email (for example if it’s lost, broken, or stolen) contact your reporting centre straight away to explain. They can record it and tell you how to report until you get access again. You can find the most recent contact details and information here.

Electronic Monitoring (tagging)

From 15 June 2022 to 31 December 2023, the Home Office ran a pilot using GPS electronic monitoring tags for certain people on immigration bail. This began under the Electronic Monitoring (EM) Expansion Pilot, using powers in Schedule 10 of the Immigration Act 2016, which allow the Secretary of State to make tagging a condition of bail for anyone who is “liable to detention.”

There is currently no clear public evidence that GPS tagging improves compliance compared to traditional reporting methods.

However, as of October 2025, Immigration Enforcement still have the power to use electronic monitoring tags and the Reporting and Offender Management (ROM) Guidance v8.0 still lists it as an option that can be used instead of, or in addition to, in-person reporting.

In practice, EM tags are GPS ankle devices supplied and managed by Mitie Care & Custody on behalf of the Home Office. They record a person’s movements 24 hours a day and send data securely to Home Office systems. People must charge the tag daily and report faults immediately. Failing to keep the tag charged or tampering with it can be treated as a breach of bail conditions, which may lead to detention.

Only GPS ankle tags are used in immigration cases. Other tag types used in the criminal justice system (for example, radio-frequency or alcohol-monitoring tags) are not used for immigration bail. The Home Office’s EM scheme is separate from the Ministry of Justice tagging system.

Action Section: Be prepared for telephone or digital reporting

- If you don’t have your own phone or email, tell the Home Office or your legal adviser as soon as possible so your bail conditions can be changed. For example, you may be allowed to report by phone from a caseworker’s device, or by going to a reporting centre instead.

- Don’t use someone else’s phone or email to report. The system is usually linked to one device, and using another person’s phone can look like you did not report.

- If your phone is lost, stolen, or broken, contact your reporting centre quickly so they can update your record.

- Make sure you keep your phone charged and it has enough battery at the time you are meant to report.

- Make sure you can hear notifications like the phone ringing or that you have received an email or text message.

- Save the Home Office numbers so you recognise the call and don’t miss it.

- Check your voicemail and SMS (text messages). Sometimes the Home Office leaves messages or sends reminders.

- Stay in a place with good signal or Wi-Fi when you are due to report. Poor signal can make you miss the call or fail digital reporting.

- Have your documents ready as you may need to provide reference numbers or information

- Tell the Home Office immediately about any changes, including a new phone number, new email or new address (even if you have moved between different accommodation provided by the Home Office).

- Set reminders: Use your phone alarm, calendar, or ask someone you trust to remind you of reporting times.

How often do I have to report?

The Home Office decides how often and in what way someone must report, based on their case type and personal situation. Reporting type and frequency are always decided on a case-by-case basis by Immigration Enforcement staff, taking into account a person’s health, family circumstances, case progress, and risk assessment.

If you’re unsure why you’ve been asked to report in a certain way or think it’s too frequent, you may be able to ask for your reporting conditions to be changed.

You can read the current suggested patterns about ways and how often someone should report in Reporting and Offender Management (ROM) Guidance v8.0 (2025). These categories reflect the latest suggested Home Office guidance and are not fixed rules.

We have also summarised the list in table below:

| Personal circumstances | Type of reporting | Suggested guidance on how often you should report |

| Adults (over 18 years old) with an ongoing asylum claim | Decision is made on each individual case | Decision is made on each individual case |

| Adults with an ongoing appeal or judicial review | Telephone with attendance in person every 3 months | Decision is made on each individual case |

| Adults with an outstanding immigration application | In-person or telephone | Every month or every 2 weeks |

| Adults with no active applications and/or barriers to removal which means the Home Office believes there is nothing stopping them from removing someone from the UK. For example, you have no ongoing applications or appeals and there are no problems getting travel documents or a passport. | In-person | Every 2 weeks |

| Adults with no ongoing applications but with “no prospect of removal”. This means adults who the Home Office cannot practically remove from the UK at the moment. | Telephone with attendance in person every 3 months | Decision is made on each individual case |

| Families with children under 18 years old | Digital | Decision is made on each individual case |

| Pregnancy | Telephone may continue | Reporting should be stopped 6 weeks before the expected week of child birth (you need to send a MATB1 form to the Home Office). |

| Foreign National Offender (FNO) – someone who is not a British Citizen and has a criminal conviction that is considered serious enough for deportation. This does not mean any criminal conviction. | In-person (even if you have an active asylum claim) | Decision is made on each individual case |

| Unaccompanied minor (under 18 years old with no guardian) | No reporting until 18th birthday | May report between 17th and 18th birthday and this will be organised with social services |

| Elderly adult The Home Office does not define this in the reporting rules. Other services in the UK define “elderly” as aged over 65 years. The Home Office Adults at Risk policy about who should not be detained refers to people over 70 years old. | Digital only unless FNO | Decision is made on each individual case |

| Adults who are “vulnerable”. This could mean that you have medical or mental health conditions that make it hard to travel to the reporting centre or make reporting unsafe. You will need to provide medical evidence. | Digital only unless FNO | Decision is made on each individual case |

Challenges of in-person reporting

Reporting in-person can be extremely difficult. It can be hard practically, but also emotionally and physically. Many people describe reporting as humiliating, traumatising, or frightening. Reporting centres are also the places where people may be detained, so it is normal to feel anxious, scared, or unsure before an appointment. You can read the experiences of others here.

There are also real barriers: long journeys, health problems, childcare, costs, or being treated unfairly at reporting centres. This section goes through some of the key practical issues and risks including travel, missed appointments, and risk of detention, and explains what steps you can take to prepare, protect yourself, and get support.

Travel assistance

If you are on immigration bail and must attend regular reporting appointments, you may be able to get help with travel costs in exceptional circumstances. You must apply directly to your reporting centre (listed on your Bail 201 form).

You can only apply for travel assistance in certain circumstances:

- If you live more than 3 miles from your reporting centre

- If you live within 3 miles, you’ll only get help in exceptional cases, such as:

serious health problems, mobility issues or mental-health conditions that make travel unsafe, or urgent childcare or caring responsibilities. You will need to provide evidence of this.

If your application for travel assistance is refused you have the right to ask for the decision to be reviewed by the ROM manager. If they refuse again, they must give their reasons in writing.

If your application is approved, the Home Office might put additional money on your ASPEN card to cover the cost of the return journey, or they might send you return travel tickets (usually bus) by post or email, or give you tickets at your reporting appointment.

If your ticket is lost or stolen it will only be replaced in “exceptional circumstances”. If the Home Office thinks you are using tickets for other reasons except attending your reporting appointments then they may stop providing you with travel assistance.

What if I cannot attend a reporting appointment?

If you cannot go to a reporting appointment, try to tell the Home Office before the appointment time. Missing a reporting event without telling them may be treated as breaking your immigration bail conditions, which can increase the risk of detention. The important thing is to make contact with them and explain what has happened.

You can ask to change or delay an appointment if you are unwell, have a medical appointment, a childcare emergency, travel problems (such as cost, distance, or disruption), an important legal appointment, or a serious personal crisis like a bereavement or a mental health emergency. Sometimes things happen on the day, and you can explain this afterwards.

Send evidence if you can, such as a doctor’s note, hospital letter, travel-delay screenshot, childcare proof, or a letter from your lawyer. Keep copies of anything you send and any correspondence from the Home Office. You can find all the contact details for reporting centres here.

The Home Office expects solicitor appointments to be arranged around reporting times, but if the appointment is essential (for example, an appeal hearing, asylum interview, trafficking/modern slavery interview, or an important legal deadline) they should offer flexibility. They do not have to change a reporting appointment for religious reasons, but may be flexible about the time.

If you cannot attend your reporting time, contact the Home Office using the phone number, email, or SMS details they have given you. Explain clearly why you cannot come, send evidence if possible, and save the new appointment time. Tell your lawyer or caseworker so they know what is happening.

If you miss an appointment without telling the Home Office, they may contact you to ask what happened. Reply quickly and provide any evidence you have.

Asking to change your reporting conditions

If you are on immigration bail, the Home Office decides how you must report, whether that is in person, by phone, or through digital reporting (IBDR) and how often you must report.

If you are experiencing serious difficulties with attending your reporting appointments or you think that it is not appropriate for your situation, you can ask for the Home Office to “vary” your reporting condition, which means changing the way you report. For example:

- You have to travel more than 1 hour (each way) by public transport to the reporting centre

- You have a physical health condition that makes it difficult to travel to the reporting centre and/or puts your health at risk

- You have a mental health condition that makes it difficult to go to reporting and/or is worsened by the reporting appointments.

- You have to use your asylum support payments to travel to reporting

- You are recognised as a victim of trafficking or modern slavery (you have a positive NRM decision).

- You have to bring children with you to the reporting centre

- You have an ongoing asylum claim or another type of ongoing immigration case then you may be able to change to telephone or digital reporting

However, the Home Office is unlikely to change your conditions from in-person reporting if they believe that:

- You are considered to be a Foreign National Offender (usually a criminal conviction with a sentence of 12 months or more)

- You are taking steps to return to your home country

- You refused or did not take up the Voluntary Return programme

- You have been identified for removal

- You missed phone or digital reporting and the Home Office lost contact with you

To make a request, you will have to provide evidence. For example: if you have to travel over 1 hour then you could provide a screenshot of the distance between your home address and the reporting centre from Google Maps. If you are making a request based on a physical health condition then you will need to provide evidence from your GP or healthcare professional.

If you have a legal representative it is a good idea to speak to them about your reporting conditions to make sure that all information sent to the Home Office is accurate and consistent.

Risk of detention when reporting in-person

There is always some risk of detention at a reporting appointment, but it is higher in certain situations. People are more likely to be detained if:

- Your immigration case has been refused or closed and you have no ongoing appeal or legal claim.

- You do not currently have an active application or legal case with the Home Office.

- The Home Office believes removal is possible soon (for example, if travel documents have been issued).

- You have been categorised as a “returns priority,” including people the Home Office says can be removed soon or people with criminal convictions.

- Your bail or reporting conditions have recently changed which may indicate that the Home Office is re-assessing your case.

- People with pending asylum claims or active judicial reviews are generally at lower risk, but detention can still happen.

The Home Office must complete a mitigating circumstances interview before they can decide to detain you. This decision must then be approved by a senior Home Office official.

A mitigating circumstances interview is when a Home Office officer asks you about anything that could affect the decision to detain you. They may ask about your family, partner, or children; any medical conditions, disabilities, or medication you need; and any mental health conditions or impairments (for example learning difficulties, psychiatric illness, or clinical depression). They may also ask if you want to leave the UK voluntarily.

If you have a mitigating circumstance interview, it is important to tell the Immigration Officer anything about your physical or mental health, and to give evidence if you can.

If you are detained at a reporting centre

If you are detained when you go to report, you will be kept in a holding room inside the reporting centre while the Home Office arranges transport to take you to immigration detention. You may be taken first to a Short-Term Holding Facility, or you may be taken directly to an Immigration Removal Centre.

The rules say you cannot be held in a holding room at a reporting centre for more than 24 hours. Your legal adviser is allowed to visit you while you are there.

A Home Office officer who is not trained to make arrests is not allowed to use force on you, unless it is needed to protect themselves or other people. In this context, “force” means any physical action used to make you move or do something, for example holding your arms, guiding you, pulling or pushing you, or using restraints like handcuffs. This includes moving you from the reporting area into an interview room or a holding room.

If you refuse to move or do not cooperate, the officer must call arrest-trained officers. These officers are allowed to physically escort you, which means holding or guiding you to another area. They may use reasonable force if they have to. This means they can use only the smallest amount of force needed to carry out the action. Officers should not use force to punish you or use more force than is necessary.

If the Home Office planned to detain you at a reporting appointment and you do not go, they may set a new time to detain you or they may send immigration officers to your home to carry out the detention.

Reporting Solidarity

In some areas, community groups have signing support systems to help people who report. Before someone goes to report, they “check-in” with the group, who keep their contact details and simple instructions on what to do if they do not come out. This helps people feel safer and means supporters can act quickly if detention happens.

A signing support system can reduce stress because the person knows someone is looking out for them and there is a plan in place.

How groups can set up a basic signing support system:

- Keep a list of when and where each member reports.

- Know where they might be held locally before being moved to a detention centre.

- Collect simple information (with consent): name, date of birth, Home Office reference, lawyer’s contact, health needs, family responsibilities, and emergency contacts.

- Ask members to sign a consent form allowing the group (or a named person) to speak to their lawyer or support them if detained.

- Decide how the group will know if someone is detained. For example, a buddy system, WhatsApp check-in, phone tree, or group email.

- Follow a clear, agreed action plan. For example, contact their lawyer, find out where they’ve been taken, support them with legal advice or bail if needed, and make sure their family, health needs, and urgent responsibilities are looked after.

Action Section: Tips for supporting someone who is reporting in-person

Reporting can be stressful and frightening. It can interrupt someone’s daily life – their education, hobbies, volunteering, work, confidence, and sense of belonging.

There are practical things you can do to support someone who is reporting; to help them feel less alone, keep them safe and prepared, and help them continue with the rest of their life alongside reporting. These are only suggestions, and it is important to ask for permission, respect boundaries, and let the person lead the way in what support feels right for them.

Below are practical steps you can take to support someone before, during, and after reporting.

- Talk about reporting. Gently starting a conversation about reporting (e.g. how often they go, when and where they report, how it makes them feel, and whether they want help with travel or reminders) can help create a safer space where they feel seen, supported, and not alone. This can make it easier for them to share worries, ask for help, or prepare for their appointment without feeling overwhelmed. These conversations can also be a stepping stone towards creating safety plans, talking about risks calmly, and helping the person feel more in control on reporting days.

- Help to recognise times of increased risk of detention: Talking about reporting regularly and building trust can help people feel more comfortable to share any changes in their immigration situation. This makes it easier to spot moments when risk might increase – for example, a recent decision on their case, a mitigating circumstances interview at their last reporting event, changes to how often or how they report (such as being moved from phone to in-person reporting), or if they have missed previous reporting appointments. These are the times to review any safety plans together and make sure everything is up-to-date and in place.

- Reporting solidarity: You can support someone by helping them set up a small check-in routine for reporting days. For example, add their reporting dates to your calendar so you can check in with them before they go in and after they come out. This can help them feel less alone.With their consent, you can also hold emergency contact details or instructions about who to call if they do not check in after their appointment. This kind of “signing support” can make reporting feel safer and more manageable.

- Communication with the reporting centre: You can help someone write a simple message or email to the Reporting and Offender Management (ROM) team if they need to change, delay, or explain a missed appointment. This can include helping them read letters or texts, draft a short explanation, or send evidence. However, asking to vary or change their reporting conditions (for example, asking to switch from in-person reporting to phone reporting) is part of their immigration case. It is safest if this request is led by a lawyer or regulated immigration adviser. Supporters can help with practical tasks like writing, sending, or understanding messages, but should not give immigration advice or decide what to ask for.

- Help with communication to others (e.g. school, college, work, volunteering) Reporting can make it hard for someone to keep up with classes, work, or volunteering. You can support them by helping write short messages or emails to explain why they need to miss or be late for something. This can stop them losing their place in college, missing important classes, or getting into trouble for reasons outside their control.

For example, you can help them send a simple message like: “I have a legal reporting appointment with the Home Office. I must attend at this time and cannot change it. I will come back as soon as I can.”

You can also help them read replies, plan their timetable, or talk to a tutor or manager with their consent.

Immigration Compliance and Enforcement (ICE)

There are ICE teams across the UK. They are organised by region, and each region has a lead officer and several office locations. One ICE team may work from more than one address. The structure has changed over the years and there is little transparency about how these teams are organised. You can see the latest contact details here. These teams carry out immigration checks, home visits, workplace raids, and other enforcement activities.

Immigration enforcement in public spaces

Immigration Officers cannot randomly stop people and ask for papers. They can only question someone if:

- They already have information about a specific person they are looking for, or a specific location linked to immigration offences (for example, a workplace or street where officers believe a named person may be found). This is called “intelligence”.

AND

- Something they see or hear gives them a real reason to suspect that a person may be breaking immigration rules.

Before carrying out a street operation, Immigration Enforcement must follow internal procedures. A manager must approve the operation before officers go out. They are not allowed to set up in public places and stop people at random.

Types of “intelligence” (information) Immigration Officers may use

Home Office guidance says public-space (“street”) operations must be planned in advance and based on real information. This can include:

Surveillance operations where officers have watched a place from a distance to confirm whether a specific person is present.

Reports from the public who contacted Immigration Enforcement and gave information about a specific person or place.

Information from other organisations such as the police, local councils, HMRC, or other government departments

Immigration Enforcement sometimes uses past information to identify places where immigration problems have been found before. This can include looking at data, reports, or what officers found during previous visits.

What is “reasonable suspicion”?

According to Home Office guidance, suspicion must come from behaviour or information, such as:

- Someone trying to hide or leave suddenly

- Answers that do not match the information officers already have

- Documents that look false

- A family member whose immigration status depends on the person being investigated

Example of when officers can ask questions

Officers have intelligence that a specific man with no current visa works at a shop. When they visit, they see someone who matches the description trying to hide in a back room. This gives a lawful reason to question him about his immigration status

Example of when officers cannot ask questions

Officers walk past a group of people who “look foreign” or have accents. They have no information (intelligence) about any particular person and no suspicious behaviour. They are not allowed to question anyone about immigration status in this situation.

Action Section: If an Immigration Officer approaches you in public

If an Immigration Officer approaches you in a public place and wants to ask questions, they should follow certain rules. They cannot use your race, skin colour, accent, clothing, or language on its own as a reason to question you.

If you are not sure what is happening, you can calmly ask:

“Am I being detained, or am I free to go?”

“What power are you using to stop and question me?”

“Can I speak to a lawyer?”

Your rights if you are stopped by an Immigration Officer

Exploratory questions (first questions)

Often the first questions officers ask are simple questions to try and get information (sometimes called “exploratory questions”). For example: “Do you live here?” “Do you work here?” “What is your name?”

• You are not under arrest at this point.

• Answering these questions is usually voluntary (your choice)

• You can ask: “Am I being detained, or am I free to go?”

• If the officer says you are free to go, you do not have to answer and you can walk away.

Examination (when officers use stronger powers)

If officers say they are examining your immigration status or doing a formal immigration interview, they are using stronger legal powers.

• You may not be free to leave while this examination is happening.

• They can require you to answer some questions about your name, nationality, and immigration status and to show documents.

• You can ask them to explain clearly what power they are using and you can ask for a lawyer.

Immigration Officers should:

• Say who they are and show their Home Office ID card

• Explain why they are speaking to you, including what information led them to approach you

• Give you a chance to explain if they believe your behaviour seemed unusual

• Record the encounter in their official notebook or device (time, place, reason, what was said)

• Inform their supervising officer about who they spoke to and what happened

• Record any concerns or complaints you raise

The police and immigration enforcement

In the UK, any police officer can stop and speak to you. If they are not in uniform, they must show you their warrant card (police ID). Police may ask simple questions such as your name, what you are doing, or where you are going. You do not have to stop or answer these questions in most situations , and refusing to answer cannot be used on its own as a reason to search or arrest you. Police can speak to you and ask questions, but they should not stop or search you just to check your immigration status or because of your race, accent, language or clothing. They need a separate lawful reason to use stop and search or arrest powers. You generally do not have to answer questions about your status in a voluntary encounter, and refusing to answer on its own should not be used as a reason to search or arrest you.

E-bikes and delivery drivers

We know from the community that Delivery riders have been targeted by immigration enforcement for a number of years now, which has been increasing. As of mid-2025, Deliveroo, Uber Eats and Just Eat now have agreements with the Home Office to use stronger ID and right-to-work checks when people sign up and share data. These are company processes only and do not change your legal rights if police or immigration officers stop you in public.

Community groups report that Immigration Enforcement sometimes appears with police during street stops, especially where riders use e-bikes. There is no public Home Office policy that allows random immigration checks on riders. Police can stop you only for road-traffic reasons. For example, they might stop an e-bike if they think it does not meet the legal rules to be classed as an electric bike. You can check these rules on the official government page here.

A police stop does not automatically become an immigration stop. Immigration Officers cannot “borrow” police powers. They need their own lawful reason before they can question someone.

Enforcement visits (immigration raids)

The Home Office claims that enforcement visits are used to check if someone is working without permission, look for someone the Home Office wants to detain, investigate suspected immigration offences or follow up information the Home Office has received. We call enforcement visits “raids” because they often feel sudden, intimidating, and involve several officers entering a home or workplace with little warning. The Home Office calls them “enforcement visits”, but in many communities we use the word “raid” to reflect the fear, shock, and loss of control people experience during these operations.

How can Immigration Officers get access to a place?

Immigration Officers have different legal powers depending on where they want to enter (a home, a business, a workplace, a licensed premises, or another type of building) and why they want to enter (to speak to someone, check identity, search for a person, or make an arrest).

There is not one single rule for all places.

Officers can only enter if:

- They have a warrant

- They have an Administrative Removal (AD) letter

- They have a specific legal power for that type of building (e.g. in places licensed to sell alcohol or late-night food.)

- They have been given permission (“informed consent”) to enter

Immigration Officers must always tell you who they are. They will normally wear full Immigration Enforcement uniform. If they are not in uniform, they must show you their Home Office ID card straight away.

If they have a warrant and are wearing full uniform with the warrant number visible, they only need to show their ID card if you ask. You are always allowed to ask.

If they do not have a warrant (for example, entering with informed consent, an AD letter, or licensing powers), they must show you their ID card before entering, unless the building is empty.

In many street encounters, initial questions are voluntary which means it is your choice whether or not you want to answer. If you have not been told you are being formally examined or detained, you generally don’t have to answer and can ask: ‘Am I being detained, or am I free to go?’”

Entry by informed consent

“Informed consent” means you choose to let Immigration Officers enter, after they have clearly told you:

- who they are

- why they want to enter

- what they want to do inside

- that you do not have to say yes

- that you can change your mind at any time

Consent only counts if it is your choice: you are not pushed or forced, and you understand what you are agreeing to.

Officers must also check that the person giving consent:

- is the occupier – this means the person that lives there or has the right to let people in. A landlord cannot give consent for a tenant.

- in shared houses, officers need consent from each room’s occupier (not just the person at the door).

- is 18 years old or over

- understands what they are agreeing to

- is not being pushed or frightened into agreeing

Warrants

Immigration Officers sometimes need a warrant. A warrant is a legal document signed by a court or authorised officer. It gives Immigration Enforcement the legal power to enter a specific place without consent.

A valid warrant must have:

- The name of the person being arrested OR

- The full address officers are allowed to enter

- it must have a date it was issued

- it must be in date on the day officers use it

- it must not be expired

- it must show the correct address or the correct name of the person being arrested

- The legal power they are using (for example: Schedule 2 Immigration Act 1971)

- A statement showing whether officers are allowed to use force to enter

- The date it was issued

- The court or senior authorised officer who signed it

- must be shown to you through a door or window if you ask

If something looks wrong (wrong name, wrong address, wrong dates or unclear authority), you can say: “This warrant does not match me or my address. I do not give you permission to enter.”

AD letter (Assistant Director’s letter)

An AD letter is a Home Office document that tells a person they are being removed from the UK because the Home Office says they do not have permission to stay. It is part of the administrative removal process, which is different from deportation.

An AD letter is not a warrant and is not signed by a court. Under paragraph 28CA of the Immigration Act 1971, an AD letter gives Immigration Officers limited power to enter a property only to arrest the person named on the letter, and only if they believe that person is inside. It does not give officers the right to search the whole home or question other people who live there, except for simple questions to help find the named person. It also does not give the wider powers that come with a court-issued warrant.

Immigration Officers use AD letters because they are quicker and easier to issue. They do not need to go to a judge or provide the same level of evidence required for a warrant. Warrants take more time, require more proof, and give stronger protections to the person, so the Home Office often relies on AD letters instead.

Forced entry

Immigration Officers cannot break into a home or business whenever they want. Forced entry is only allowed in very limited situations, and only when the law gives them the power.

With a warrant:

If officers have a court-signed warrant that allows the use of force, they can break a door or lock only to enter the property. This does not automatically allow them to search other rooms unless the warrant or another legal power gives this.

With an AD letter:

An Administrative Removal (AD) letter gives a limited power to enter only to arrest the person named in the letter. Forced entry is allowed only if the person named on the AD letter lives or stays at that address, and officers have a reasonable belief that the person is inside right now. If the person is not inside, or if officers do not have reasonable belief they are inside, they cannot force entry using an AD letter.

In an emergency (very rare):

Officers can force entry without a warrant or consent only to save a life or prevent serious harm. This is an emergency situation similar to those faced by fire or ambulance services. It must be an immediate risk, such as someone inside being in danger.

Summary table of ways immigration officers can enter a place

| Location | Ways immigration officers can enter |

| Private home For example: houses, flat and rooms in shared houses | A valid warrant With informed consent from the person living there – not a landlord Officers cannot go into your back garden unless they have a warrant, an AD letter, your informed consent, or there is an emergency. |

| Business or workplaces (not licensed). For example: offices, warehouses, factories, car washes, nail bars, restaurants without alcohol licences | A valid warrant With informed consent from someone with authority e.g. the manager, supervisor, business owner, person in charge. Or whoever appears to be in charge. |

| Licensed premises – this is any place that has permission from the local council (a licence) to do certain activities. In places licensed for alcohol or late-night hot food (11pm–5am), For example: a bar, nightclub, supermarket selling alcohol, takeaways | Without a warrant, as “authorised persons” under section 179 of the Licensing Act 2003. They may still use a warrant if they want to They do not need consent Cannot enter private living areas |

Answering questions from immigration officers

Immigration Officers can ask questions in different ways. It is important to know what kind of questioning is happening as your rights are different in different situations.

First questions: “exploratory questions” (voluntary)

At the beginning, officers may ask simple questions like “Do you live here?”, “Do you work here?”, “What is your name?”. These are usually exploratory questions.

- You are not under arrest.

- These questions are generally voluntary.

- You can ask: “Am I being detained, or am I free to go?”

- If you are free to go, you do not have to answer and you can walk away.

- Officers should not detain you only because you refuse to answer these informal questions, but they may still decide to detain you if they already have other information about you.

Formal immigration examination

If officers say they are examining your immigration status under immigration law, they are now using stronger legal powers.

- They may say you are being held for an immigration interview or examination.

- You may not be free to leave while this formal examination is happening.

- They can require you to answer some questions about your name, nationality, and immigration status and to show documents.

- You can still ask for a lawyer and support, and you can ask officers to explain clearly what power they are using.

Detention or arrest

You are detained only when an officer clearly tells you that you are not free to leave.

- If you are detained or arrested, officers must tell you why.

- They may then ask you more questions about your immigration status, or, if they think you may have committed a crime, the police must follow criminal law rules (a caution, the right to free legal advice, recorded interview).

Being inside a building is NOT the same as detention

Immigration Officers entering a home, workplace, or licensed premises does not automatically mean you are detained. Even with a warrant, an AD letter, or special powers for a licensed premises, officers must still tell you directly if you are being detained. Until they do, you are usually free to move around and leave, and answering questions is generally voluntary. You can always calmly ask: “Am I being detained?” “Am I free to leave?” “Can I speak to a lawyer?”

Police questions and immigration status

In the UK, police can stop and speak to you and ask simple questions like your name or what you are doing. In many situations you do not have to answer, and refusing to answer simple questions on its own should not be used as a reason to search or arrest you.

Police should not stop or search you just to check your immigration status, or because of your race, accent, language, or clothing. They may ask about immigration status after an arrest, or where there is another legal power or a joint operation with Immigration Enforcement, but you still have rights and can ask for legal advice.

Action section: If Immigration Enforcement come to your home or workplace

When Immigration Officers come to your home or workplace, it can be a shocking and frightening experience. Raids can happen early in the morning, in front of neighbours, children or colleagues. It is normal to feel scared, confused or angry. You still have rights, and you still have choices.

Try to stay as calm as you can. Officers must act professionally, explain who they are, and show respect.

| Situation | Your rights | What you can say |

| Immigration Officers come to your door | Officers must identify themselves. If they do not have a warrant, they must show their Home Office ID card. | “Who are you?” “What legal power are you using to enter?” “Can I see the warrant or AD letter?” |

| If officers say they have a warrant | You can: – Read the warrant through the door or window – Check the name, address. date, how long warrant is valid for and how many times allowed to use the warrant. – Check if forced entry is allowed – Take a photo if it feels safe A real and valid Home Office warrant must show: the correct name (if arresting a person) or the exact address; the legal power being used; whether forced entry is allowed the date issued and the signature of the authorised senior officer; it must be in date and not expired | “Please show me the warrant so I can understand the information” If the name, address or dates are incorrect, you can say: “This warrant does not have the correct details. I do not give permission to enter.” |

| If officers use an AD letter instead of a warrant | An Administrative Removal (AD) letter – names a specific person – gives only a limited power to enter to arrest that person – is not a court warrant Officers can only force entry with an AD letter if they reasonably believe the named person is inside right now. | If the name is wrong, you can say: “The person on this letter does not live here. I do not consent to entry.” |

| If Officers come to your private home and do NOT have a warrant or AD letter (entry based on consent) | To enter your private home without a warrant or AD letter Officers need: – your fully informed consent to enter. – Only the person who lives there (tenant, lodger, homeowner) can give consent. – You have the right to say no. – You can ask questions first. – You can change your mind at any time. | “Can you explain in simple words why you need to come in?” “Do I have to let you in, or can I say no?” “Who gave you permission to come in? I live here and I do not consent to entry.” “Can I speak to my lawyer / a support worker / a friend before I decide?” “Right now, I do not consent to entry.” |

| If officers come to a licensed premises (a place that sells alcohol or late-night hot food) | -Can enter without a warrant, AD letter or consent but for the business areas only – not private living areas. – Unless you are clearly told you are detained or formally examined under immigration law, you do not have to answer questions about your status. | “Are you here under licensing powers or immigration powers?” “Are we being detained, or are we free to leave?” “Are you allowed to go upstairs / into the living area?” |

| Immigration Officers leave without taking anyone | If officers left any letters or documents, you can ask a lawyer or support group to explain what they mean. Officers may come back another day, possibly with a warrant or AD letter, so it is important to get advice and make a safety plan. | To officers before they go (if it feels safe): “Can you tell me your names and office?” “Can you explain why you came today?” “Are you planning to come back, and what papers will you bring?” |

| You are the person being examined or detained | Officers should: – Tell you that you are detained or being formally examined under immigration law- Explain why, and show you their ID if you ask. You have the right to: – ask for an interpreter if you do not understand – ask for legal advice. – You do not have to sign documents you do not understand or agree with. | “Am I being detained, or am I free to go?” “I’d like to speak to my lawyer / a legal adviser before answering questions.” “Can you tell me exactly what power you are using to question or detain me?” |

| Officers take someone away | You can ask questions – because of data protection rules, officers might not answer every question or share personal information without the person’s permission. You do not have to answer questions about your own immigration status unless you are detained or formally examined. | “Where are you taking them? If you are allowed to say, is it a police station or a detention centre?” “Can you give me your name and which Home Office team you work in?” “Please make sure they are given their papers. If they agree, can I take a photo of the papers for their lawyer?” “What phone number or email should their lawyer or support group use to contact your office or the detention centre?” |

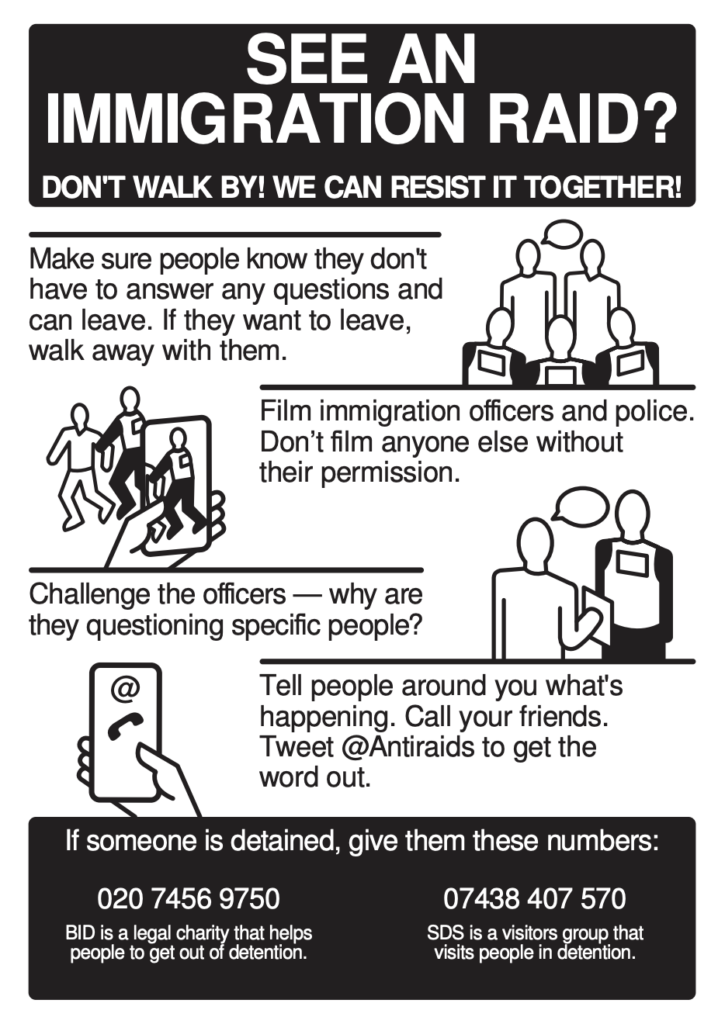

The Anti-Raids Network

The Anti Raids Network (ARN) is a loose, volunteer-led network of groups and individuals who share information and resources to help communities resist immigration raids. It is not one organisation and has no leaders. Instead, people work together to spread practical knowledge about people’s rights, support neighbours during enforcement visits, and challenge immigration controls on the street. ARN focuses on mutual aid, direct action, and solidarity, helping communities stay safe, informed and connected.

There are anti-raids groups across the country, and each uses different methods to support their communities. It’s important to remember that this work is not only about blocking a van. It’s also about preparing people long before a raid happens: building local solidarity, strengthening neighbourhood networks, and making sure everyone knows their rights. When communities are informed and connected, we are far less likely to reach crisis moments in the first place.

Action section: What to do if you see a raid

When Immigration Enforcement targets someone in our communities, there is often no one else who will step in. We keep each other safe. Your presence can make the difference between someone being taken away quietly, or someone knowing their rights and staying free.

You do not have to intervene in a confrontational way. Simply staying nearby, watching, and making sure the person knows their rights is already powerful community protection.

Talking to the person being stopped

If your own situation is safe, and the person seems open to support, a calm friendly presence can help.

You can remind them:

- “You do not have to answer immigration questions unless you are being formally examined or detained.”

- “If you are not under arrest and the officer says you are free to go, you can leave.”

- If they choose to walk away, you can walk with them.

Some people may be unsure or frightened. If they aren’t sure whether to trust you, you can say:

- “You can ask the officer to confirm what I said.”

- Offer them a physical Anti-Raids flyer if you have it, as some people find it easier to trust written material.

Let others nearby know what is happening

You can calmly explain to bystanders that this is an Immigration Enforcement stop and share basic rights information. If safe, you can contact local support groups or others who may be able to help.

Filming the interaction

You can film Immigration Officers and police from a safe distance. Filming can:

- help create a clear record of what happened

- support someone’s legal case later

- make officers more likely to follow their own rules.

Officers can ask you to stop filming, but:

- They should not force you to stop filming just because you are recording them, as long as you are not getting in the way.

- They must not delete images or footage from your phone or camera.

- In some situations, police may seize a phone or camera if they reasonably believe it contains evidence of a crime, but they still should not delete footage.

Filming is not the same as obstruction.

- Filming on its own is not obstruction.

- Obstruction means actively and unreasonably getting in the way of officers doing something they are legally allowed to do – for example, physically blocking them, grabbing them, or repeatedly interfering with their actions.

- To reduce risk, try to keep a safe distance and do not physically block officers or vehicles

- If officers say you are “obstructing”, you can calmly ask: “Can you explain how I am obstructing you? I am just filming.”

You should also think about other people’s privacy and safety. If you are filming:

- Try to focus on officers, not the person being questioned or detained, unless they say it is okay.

- Avoid sharing footage online without the person’s consent, especially if it could put them at further risk.

What officers should say to bystanders

Officers are only supposed to say: “This is an Immigration Enforcement visit.”

They must not:

- share private information about someone’s immigration status

- identify the person unless absolutely necessary

- argue about someone’s case

- give misleading information

If someone wants to complain, officers must give information on how to do that.

Other people inside the premises

If officers enter the premises by consent:

- People inside can usually move around freely.

- People can leave the building unless they are told they are detained or under arrest.

- People do not have to answer immigration questions unless they are being formally examined or detained.

- Officers should not block exits or stop people leaving, unless they say the person is detained or under arrest.

They may ask people to stay in one area, but this is a request, not a legal order, unless someone is actively and unreasonably obstructing them.

Video: Fighting back against immigration raids as a community

Leeds Anti-Raids Action have created a video of their training designed to help people feel more confident about the basics of immigration raids: what they are, how to spot them, what your rights are, and the wide range of ways communities can resist and keep each other safe.