Last updated: 1 October 2024

Claiming asylum is an application you make to get a type of international protection. While you are waiting for a decision on your claim, you are an asylum seeker. If your claim is accepted, you will receive a grant of refugee status, and be classed as a refugee.

Refugee status can be given to you by another country if you fear being returned to your country of origin or residence. You need to fulfil specific requirements in order to have your asylum claim accepted. You can read more about them on this page.

To learn more about entering the UK to claim asylum, click here.

On this page, you will find the following information:

Click on the buttons below for translated summaries of this page:

Video in other languages:

What is an asylum claim?

Asylum is defined in the Refugee Convention 1951, an international law which the UK signed many years ago.

Asylum is the claim you make, and if that claim is accepted by the country you claimed asylum from, you become a refugee and receive international protection.

You claim asylum from the Home Office in the UK. This is the government department responsible for immigration, borders and security.

According to the Refugee Convention, a refugee is:

…someone who is unable or unwilling to return to their country of origin, owing to a well-founded fear of being persecuted for reasons of race, religion, nationality, membership of a particular social group, or political opinion.

This definition includes a lot of important words/concepts that you should understand before claiming asylum. Keep reading to learn more.

Well-founded fear

To succeed in your asylum claim, you need to show that you have a “well-founded fear” of facing persecution if you were returned to your home country. This means you do not need to show that the persecution would definitely happen, but that there is a real risk it could happen.

If you experienced persecution in the past, this does not necessarily mean you will get refugee status. You need to show there is a future risk of persecution.

To show this fear is well-founded, you will need to provide evidence (this means proof). Read our Toolkit page about evidence to learn more.

You might have to think creatively about how to gather evidence for your asylum claim. For example, are there people who witnessed things that happened to you? Have you got documents that prove any part of your story? These might include arrest warrants, court documents, letters from friends/organisations showing you are in danger. Is there newspaper coverage of an event you are talking about? Are there human rights reports that show the situation in your country is like you say it is?

In many people’s cases the UK Home Office will not believe your story. Or, if your claim is refused by the Home Office, and are able to go to court and appeal that refusal, the judge may also not believe your story.

You should try to obtain other evidence to support your story. You should not wait for the Home Office or courts to say they do not believe you before you try to get evidence to support what you have said.

Persecution

In an asylum claim, the legal definition of persecution is ‘serious, targeted mistreatment’ of an individual because of their identity under one or more of the following specific grounds:

- race

- religion

- nationality

- political opinion

- membership of a particular social group (this is explained below)

The rules that the Home Office use to decide asylum claims say that persecution is an act that is sufficiently serious by its nature (this means on its own) or repetition (this means if it happens more than once) as to constitute a severe violation of a basic human right. Persecution could also be an accumulation (this means a build-up) of various measures which would make it sufficiently serious.

You may be at risk of persecution because of imputed identity or beliefs. This means what people think you are or do. What people think about you could put you at risk of persecution even if it’s not true. For example, if your local community thinks or says that you are gay or lesbian, you might be at risk even if you are not. Or, you may not actually be a member of a political group, but someone might spread rumours that you are to try and get you into trouble.

Your asylum claim is your application for protection in the UK from this persecution. You need to explain, through your own words (spoken and written) and evidence, that you fear returning to your country. You need to say what you think will happen to you if you go back. For example, who would do this to you? Why would they do this? Why do you think this will happen to you? Have things happened to you in the past? Have things happened to people you know or people like you?

The rules say that examples of an act of persecution could include (but there may be other actions that are not in this list):

- an act of physical or mental violence, including an act of sexual violence

- a legal, administrative, police, or judicial measure which in itself is discriminatory or which is implemented in a discriminatory manner

- prosecution or punishment which is disproportionate or discriminatory

- denial of judicial redress resulting in a disproportionate or discriminatory punishment

- prosecution or punishment for refusal to perform military service in a conflict, where performing military service would include crimes or acts falling within the grounds for exclusion (meaning a crime against peace, a war crime or a crime against humanity)

Discrimination is not the same as persecution, but if it is repeated or is very serious, it may then be considered persecution.

Many people seeking safety in the UK are fleeing civil war or widespread violence, which is not individual persecution because of their identity.

If the risk to you isn’t specific persecution, you may be considered for a different kind of protection. See the Humanitarian Protection section below.

Particular social group

‘Particular social group’ is the most complicated area of the Refugee Convention grounds for claiming asylum. This is because it is quite vague and can cover a variety of situations. This category relies on previous asylum legal cases that have been used to define what are now recognised particular social groups.

It is important to note that gender and sexuality are not distinct Refugee Convention persecution grounds, but instead come under a particular social group. Gender alone is not a particular social group. For example, an example of a particular social group for gender would be “women at risk of domestic violence in Pakistan”, or “gay man from Iran”.

In 2022, a new law called the Nationality and Borders Act came into force in the UK. Section 33 of the Act changes the definition of a particular social group slightly. Before this law came into force, people trying to show that they are from a particular social group and claiming asylum in the UK only had to fulfil one condition in the legal test.

Now they must fulfil both conditions under Section 33 of the Act:

The first condition is that members of the group share—

(a)an innate characteristic,

(b)a common background that cannot be changed, or

(c)a characteristic or belief that is so fundamental to identity or conscience that a person should not be forced to renounce it.

(4)The second condition is that the group has a distinct identity in the relevant country because it is perceived as being different by the surrounding society.

So, to be part of a particular social group for the purpose of an asylum claim in the UK, you must share a feature with the group you claim to be part of (under the first condition), and the group must be recognised in the country you are fleeing because of how ‘different’ it is perceived to be (under the second condition).

Who are you at risk from?

You may fear persecution from your country and/or its agents, such as the army, government officials, or the police. If this is the case, it is clear why you would be “unable or unwilling” to seek protection from persecution, because it comes from your country.

However, you may fear persecution from people that aren’t officially recognised as agents of your country, but who have a lot of control in the country, or part of the country. For example, Al-Shabaab in areas of Somalia, or ISIS in Iraq. Again, this should be fairly simple to explain why you cannot get protection from the country in these circumstances, because the country cannot protect you from them.

Persecution might also come from “non-state actors”, such as a member of your family or community, a gang, religious, or political opponents.

To qualify for Refugee Status because you fear persecution from a non-state actor, you must show that you cannot be protected from this persecution by the state. ‘This may be because there is no protection available from your government, or it may be that asking for protection would put you in danger.

Sur place claims

‘Sur place’ literally means ‘on the spot’ in French. Under rule 339P of the UK Immigration Rules, a sur place claim is when:

339P. A person may have a well-founded fear of being persecuted or a real risk of suffering serious harm based on events which have taken place since the person left the country of origin and/or activities which have been engaged in by a person since they left the country of origin, in particular where it is established that the activities relied upon constitute the expression and continuation of convictions or orientations held in the country of origin.

So, a person can bring a sur place asylum claim if events have happened or they have taken actions since they left their country of origin that would give rise to an asylum claim (well-founded fear of persecution if they were returned).

For example, if someone who has always been opposed to their government leaves their country, and once they have left, they begin to openly oppose the dangerous government. Or, if someone has always been gay, but only feels safe enough to come out once they reach the UK.

Internal relocation

Another factor that the Home Office will consider when deciding whether to grant you refugee status is whether there is somewhere else in your country – outside of your city/region – where you could go and be safe. This is called internal relocation.

The Home Office may accept that you would be at risk in your home region of Afghanistan but argue that you would be safe if you relocated to the capital Kabul. Or they may accept that you may be at risk of persecution because of your clan identity in the capital Mogadishu, but argue that you would be safe in Somaliland because your clan has protection from a majority clan there.

To show that internal relocation is not going to protect you, you would either need to prove that the risk you face would follow you to where you were relocated (e.g. you would be tracked down by those trying to harm you), or that you may be safe from persecution but would face other risks.

For example, this may be because you have no family or social networks in the place it is being suggested you could internally relocate to, and could not safely begin a new life there.

Economic and social factors could be considered here – would you be able to make a living if you didn’t know anyone and had no social, religious, or ethnic connections? If you couldn’t make a living, what would happen to you?

The Home Office (and the courts, if you appeal) will consider whether asking you to relocate within your country would be “unduly harsh” (this means extremely difficult).

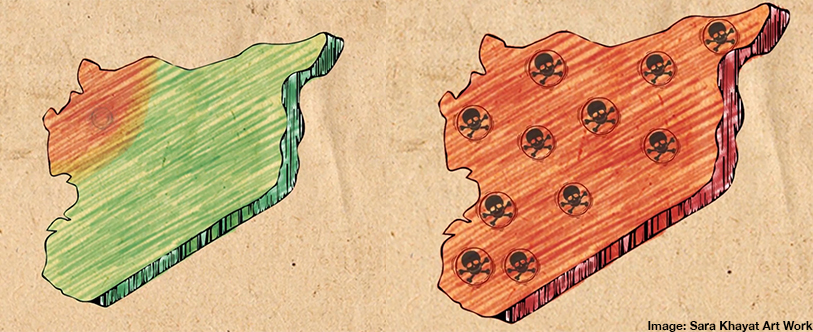

Humanitarian protection

If you are fleeing war or widespread violence that harms or could harm many people – not you specifically because of your identity – you may not qualify for Refugee Status.

You may instead have your case decided under a different part of the Refugee Convention that provides protection where there is:

“serious and individual threat to a civilian’s life or person by reason of indiscriminate violence in situations of international or internal armed conflict.”

This is called Humanitarian Protection, and includes situations where civilians are at serious risk simply by being present in a place of armed conflict or where general violence is widespread. Very few situations meet this definition, but if they do then Humanitarian Protection may be granted. You can learn more about Humanitarian Protection in our Toolkit.

How the Home Office decides asylum claims

When you claim asylum, the Home Office will consider what you say in:

- The screening interview

- The substantive (big) interview, and

- Any evidence you have provided in support of your claim.

They will use this information to decide if they think you have a well-founded fear of specific persecution (asylum) or more widespread violence (humanitarian protection). They will decide if that persecution falls under one of the Refugee Convention grounds listed above.

They will also consider whether you could be protected from harm by your own government, or whether you could live somewhere else in your country to be safe. As well as looking at the records of your interviews and any statements or evidence you give to them, the Home Office will use their own guidance documents about conditions in your country to make their decision.

Exclusion from protection

In some cases, the Home Office may take the view that a person should be excluded from protection under Article 1F of the Refugee Convention.

Article 1F states that the provisions of the Refugee Convention do not apply where there are serious reasons to consider that an individual:

a) has committed a crime against peace, a war crime, or a crime against humanity, as defined in the international instruments drawn up to make provision in respect of such crimes

b) has committed a serious non-political crime outside the country of refuge prior to admission to that country as a refugee

c) has been guilty of acts contrary to the purposes and principles of the United Nations

For example, this can happen in cases where the person has committed a serious criminal offence, or where the Home Office considers they may have been involved in human rights violations in their country of origin. This is a broad definition, and can extend to people who were employed in a wide range of roles in the government in their countries of origin if that government was involved in human rights abuses.

Someone can also be excluded from refugee status if they commit a serious crime in the UK and are sentenced to a prison sentence of 12 months or more.

One stage of the process where the Home Office will try and find out if the exclusion applies to you is during the screening interview. They will ask you questions about criminal convictions, arrest warrants, involvement in terrorism, detention as an enemy combatant, and encouragement of hatred between communities.

If the Home Office raises an exclusion in your case, or if you feel it is a possibility, it is very important to seek legal advice. You can appeal against being excluded from Refugee Status or Humanitarian Protection. Even if an exclusion is upheld, you may be allowed to stay if could be at risk of torture, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment if you were returned.